Where Great Docs Are Affordable For Everyone

As Hawaii hospitals face a financial crisis and cut services, the importance of the state’s 13 community health centers grows. And they provide toprate health care

By Alice Keesing

E-mail this story | Print this page | Archive | RSS |

Del.icio.us

Del.icio.us

Dr. Loo checks Austin Torralba’s

teeth

from helping his patients.

“I never say we can’t help you,” he says. “We never abandon a patient.”

Dr. Beatrice Loo Pediatric dentist, KalihiPalama Health Center

Don’t let Beatrice Loo catch you putting soda in your baby’s bottle. Or giving your young kids candy or gum. As a children’s dentist, Loo knows only too well the damage that can result, so she’ll have no qualms about scolding you.

Hawaii’s children have the worst rate of tooth decay in the nation, and the Kalihi-Palama Health Center is one place where you can see the sad reality of that oft-quoted fact.

“We don’t have enough dentists across the state willing and able to take care of indigent people,” Giesting says. “The teeth of our kids really are rotten, literally, and the kids who are most likely to go to the community health centers - Pacific Islanders, Native Hawaiians, Southeast Asians - are the worst of the lot.”

As Kalihi-Palama’s pediatric dentist, Loo routinely sees young children whose mouths are rotten before they even start school. She has pulled decayed baby teeth from a 13-month-old. She has capped 16 teeth in a 4-year-old. And sent children to the hospital because their mouths are dangerously infected and swollen.

The things Loo sees can be heartbreaking, but like others who work in the state’s community health centers, she is there to make a difference, one small mouth at a time.

Loo, who made Honolulu magazine’s “Best Doctor” list last year, comes from a family of dentists. Her husband, Raymond, is one, as are her eldest son and his wife. And her youngest son is thinking about entering the field, too.

Loo works part time with her husband in their private practice, but it’s her time at Kalihi-Palama that she finds particularly rewarding.

“I enjoy working on the ones who really need the help,” she says.

Located on North King Street, the Kalihi-Palama Health Center serves a large immigrant population, which is perhaps best illustrated by the fact that it has translators on staff who speak 17 languages from Ilocano to Mandarin to Chuukese.

The center is currently raising money to upgrade its facilities. Kalihi-Palama is bursting its urban seams as it tries to help all those who need it. Its adult dental services have a three-month wait, and its behavioral health services are currently located in a renovated shipping container.

Luckily, Loo says, there isn’t a wait for children’s dental appointments, and she will sometimes work through her lunch hour to make sure everyone gets seen.

Loo believes the bad state of our children’s teeth is partly attributable to the lack of fluoride in the water, but a huge share of the blame goes to sugary diets and those baby bottles full of soda.

“Sometimes new immigrants aren’t educated,” Loo says. “The grandparents give them a lot of candy. We have to educate them - you look at the parents and they have bad teeth, too.”

By the way, Loo says it is all right to chew gum that has xylitol in it, a sugar substitute that hinders the cavity-causing bacteria. And Gummy Bears are OK in her book, too, because they don’t stick to the teeth.

Often, Loo is reminded that her young patients are dealing with much more than just painful teeth. She recalls a 3-year-old boy who came in recently. He and his parents were homeless, he was covered in bites from bed bugs and his teeth were infected.

“That was really heartbreaking,” she says. “I looked at him and said, you know teeth are minor when you think about it, when you have no roof over your head, you don’t know what you’re going to eat.”

When the family left, Loo gave them extra toothbrushes and floss and toothpaste. “I just wanted to do whatever I could to help them,” she says.

Kauila Clark Hawaiian healer and board member, Waianae Coast Comprehensive Health Center

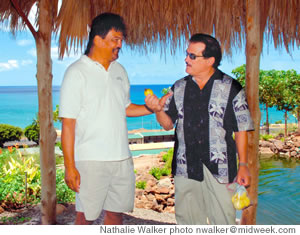

Kauila Clark, left, with Waianae CEO Rick Bettini, sample

lilikoi given to them by a grateful patient

Kauila Clark walks through the medicinal gardens at the Waianae Coast Comprehensive Health Center. He stops to pick some awapuhi ginger and squeezes it for the fragrant juice that can be used as a shampoo. He touches an awa bush, which can take the pain from a toothache. He points to a noni tree, which is used to heal everything from high blood pressure to joint pain.

Clark is a Hawaiian healer at the Waianae health center, where the ancient traditional practice has an equal place alongside the most advanced Western medicine. Sitting amidst the medicinal garden is the sparkling new Wellness Center, where the staff uses wireless laptops, giving them control of the latest in digital medical record keeping.

Clark has also served on the board of the health center for 18 years. It’s an important fact, he says, that 51 percent of community health center board members must be those people who use the facility. That’s how they ensure they deliver the kind of care that residents want - and will therefore use.

“The ultimate challenge that we face is having people take responsibility for their own healthcare, not their doctors,” Clark says. “And until then, they’re going to pay dearly.”

The Leeward Coast racks up some of the worst socio-economic and health statistics; residents struggle with drug problems, teen pregnancy, diabetes, obesity, poverty. The holistic approach taken by the center is designed to drive a wedge into those ills.

At the recently opened Wellness Center, Malama Ola, patients can visit their doctor, then also see a dietitian, a physical therapist, an acupuncturist or a psychologist. And then they can pop into the gym for a workout or exercise class.

“There is so much that can be helped with diet and exercise rather than expensive intervention,” says CEO Richard Bettini.

Using this integrated model of care, the center already has gotten some diabetes patients off insulin, Clark says.

Waianae’s expansive goals and dreams go far beyond treating just the individual patient. It’s treating the area’s economy, too. The poverty and lack of opportunities on the Leeward coast are the well-spring of many of the health ills, they say. This year, the center will put its 1,000th Leeward resident through a program that trains them in everything from medical transcription to community health work.

“Eighty percent of them have gone on to work, and these are people who were unemployable before,” Bettini says.

The center also works on the spiritual plane, a fact that permeates the very grounds - the mere sight of them is good for the soul. The gardens are lush with hibiscus and ginger, the culinary gardens provide fresh, organic tomatoes, lettuce and taro for the restaurant, the herb gardens are redolent with lemongrass, basil and allspice and the healing herbs. It’s not surprising that the center recently won a landscaping award for best commercial garden.

“Waianae does not have the best reputation, but you come up to the community health center ...” Clark gestures at the vista. “You’d usually expect to see something like this in Kahala.”

He and Bettini lead an enthusiastic tour of a new trail that winds its way into the back of the center’s 17 acres. Still under construction, the turtle trail - named after a recalcitrant rock on the path that would not be moved - is a physical, educational, historical and cultural experience.

Along the path are petroglyphs based on the Hawaiian creation chant, the Kumulipo. The petroglyphs were carved by Clark, who also happens to be an artist whose work can be found in the Smithsonian and around the world. The trail will also tell the history of the health center, which is the oldest in the state. It is all set among more beautiful gardens, with sculpted copper gates, a fountain, waterfall and rock walls.

Bettini and Clark stop at an out-cropping, the future site of the Hawaiian healers house.

Clark takes in the tawny bulk of Puu Maili behind him and the sweep of the turquoise ocean in front. “If you don’t feel good when you come up here, then you should start to feel good just by being here,” he says.

So it is, thankfully, at each of Hawaii’s 13 community health centers.

Page 2 of 2 pages for this story < 1 2

E-mail this story | Print this page | Comments (0) | Archive | RSS

Most Recent Comment(s):