Where Great Docs Are Affordable For Everyone

As Hawaii hospitals face a financial crisis and cut services, the importance of the state’s 13 community health centers grows. And they provide toprate health care

By Alice Keesing

E-mail this story | Print this page | Archive | RSS |

Del.icio.us

Del.icio.us

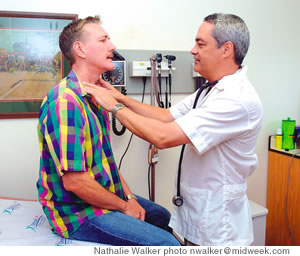

Dr. Elliot Kalauawa examines Michael Burnett at the Waikiki

clinic

For years, Hawaii’s community health centers have been our medical safety net, scooping up those who fall through the cracks and giving them the health care that many of us take for granted.

And the need for them has never been greater. The number of people using the health centers increased 33 percent between 2001 and 2005. And with dire predictions of a collapse in the private healthcare system, the centers are bracing for another new wave of need.

“The health centers are always picking up the pieces and, the way things are now, the whole system is ready to crumble,” says Beth Giesting, CEO of the Hawaii Primary Care Association, which represents the state’s 13 health centers. “We need to find ways to do more.”

The centers serve more than 80,000 people on five islands, providing medical, dental and behavioral health services. Their doors are open to all, but a primary goal is to help those who are uninsured and on the margins of society. They also provide for those who just don’t see eye to eye with the mainstream medical system. They have become places where traditional Hawaiian healing rubs shoulders with Western medical care, where immigrants can go to talk to someone about their healthcare in their own language, where patients often find a sense of family.

Because of the relationships the health centers have with their communities, they offer an ideal staging point to fight the rising tide of chronic diseases like diabetes, and health challenges such as obesity. These days, they also play a vital role in the watch for the bird flu because they cater to a large number of immigrants.

For all that they already do, those who work within the health centers are always trying to do more. Telemedicine is one new alternative being explored as a way to bring patients closer to the specialist services they need.

Because they often work with people who are struggling in life, health center employees have to be tough to manage the things that can walk through their doors.

“The health centers have to deal with all kinds of things that Joe Public doesn’t even know exist,” says Giesting, who remembers one particularly heartbreaking case where a family of Vietnamese children was being bitten by rats.

“There may be a public perception among some that the people who work at the health care centers are the losers, the slackers, the ones who couldn’t find a really good job,” Giesting says. “But the fact of the matter is that because of the complicated nature of the people they are seeing, the providers there have to be very sharp, they have to be alert to a lot more possibilities, and they have to rely on better cognitive skills because they can’t order every test there is because the patients can’t pay for it. So they really are a top-notch bunch. If they’re not, they can’t last.”

This week, as the nation marks Community Health Center Week, MidWeek shines the light on three of those who are making a difference.

Dr. Elliot Kalauawa medical director, Waikiki Health Center

Dr. Elliot Kalauawa’s patients call him the best doctor in the world.

For 20 years, Kalauawa has served as medical director of the Waikiki Health Center, one of Hawaii’s grittiest urban medical scenes.

Just two blocks from the playground of Waikiki beach, in an old building that used to be a nun’s convent, the health center is a kind place in the tough world populated by those on the margins of society.

“Waikiki, I think, even more than anybody else, sees those patients who are kind of the untouchables,” Giesting says. “They see the sex trade workers, they see the transients, the runaway kids, they see the ones who are real social misfits as well as economic misfits. And Elliot is just a sterling character.”

Kalauawa thrives on the work. “I’m completely comfortable with these people because that’s where I come from,” he says, describing a childhood that was colorful, to say the least. He grew up in Palolo Housing with his single mom, who was on welfare.

Kalauawa remembers being 10 years old and waiting, waiting, waiting in the waiting room at Queen Emma Clinic and thinking that there must not be enough doctors to look after everyone. From then on, it became his goal to be a doctor.

His smarts won him a scholarship to Iolani in the ninth grade but the plan was almost scuttled because his mom couldn’t afford the lunch, which would have cost more than $1 a day compared to the 25-cent public school lunch. But the Queen Liliuokalani Children’s Center came to the rescue; every month it sent Kalauawa a check to pay for his lunch.

Kalauawa has gone on to become one of Hawaii’s finest physicians, according to Dr. Ben Young, executive director of the Native Hawaiian Center for Excellence at the UH John Burns medical school. Young gives Kalauawa kudos for his decision to help those in need rather than following a more lucrative private practice.

Kalauawa has built a reputation as one of the most notable HIV doctors in the state. He’s also known as something of a character. He has a great rapport with his patients and, even though he might have diagnosed them in a few minutes, his consultations are never rushed. He loves to talk story and jokes that sometimes it’s his patients who are trying to make it a speedy visit.

The center saw a 36 percent increase in patient visits in the last two years, and that’s expected to grow another 9 percent this year. Fifty percent of its patients are uninsured, but there are many who go there because they like the style of medicine and because no one else is good enough after Kalauawa has treated them.

He has patients who travel from the Neighbor Islands to see him. And he likes to talk about a millionaire who walked in off the street one day and liked the place so much that he kept coming back to Hawaii to see Kalauawa for his checkups.

One thing that his job has taught him is that, rich or poor, everyone looks the same when they have their clothes off.

“We treat everyone with respect here,” he says.

The toughest part of the job is when a patient needs specialized care such as oncology or cardiology that the center cannot provide and that the patient just cannot afford.

“Sometimes I tell people that, even though we’re here in Hawaii and probably in the richest country in the world, practicing here at times is like being in a Third World country because patients have so much trouble accessing care,” Kalauawa says.

But he never lets that stop him

Page 1 of 2 pages for this story 1 2 >

E-mail this story | Print this page | Comments (0) | Archive | RSS

Most Recent Comment(s):