Fallen Heroes: Resting In Weeds

Sinking headstones and poor maintenance are just the start of the problems at the State Veterans Cemetery in Kaneohe

In this place slumbers

From season to season

The warriors of Hawaii

They gave

To all of us

Freedom

So we always remember

The place where our bones

Came into being (Birth Place)

Hawaii

(Author Unknown, engraved on the entrance to the Hawaii State Veterans Cemetery)

In ancient Hawaiian times, the remains of the dead were considered sacred, their burial places holy. Today at the Hawaii State Veterans Cemetery the remains of warriors — soldiers who fought in battles for their country and their loved ones — still remain on unsettled grounds.

With headstones sinking, weeds and a leaking sprinkler system, it is a difficult sight for those who visit the graves. It is an even bigger problem for those who try to battle against the many environmental factors affecting this cemetery.

Jane Fujimoto waters and fertilizes the ground in which her husband is buried. “He was stationed in Japan, Okinawa and in the Vietnam War,” she says. “He was in Vietnam for a year, and he spent two years in the Pentagon, only to get pancreatic cancer.”

As Fujimoto sits on the grass she planted at the grave, she and her son, Clayton, weed in the morning sun. Silverhaired, and with a look of concern and remembrance, she works diligently to take out the weeds and fertilize her precious garden.

“If you don’t water it, it gets dry and the soil is not really compacted. I had to tell them, the staff at the cemetery, to lift the stone because it kept sinking during the heavy rains. It was terrible when the rains came because my husband’s stone sunk. But the staff here has been nice to me, and they put more dirt and lifted it up.”

Unfortunately for Fujimoto and others with loved ones buried here, the grounds are still unsettled. Keeping their gardens flourishing and the stones from sinking has been a chronic problem.

Arthur Kaneakua visits his wife’s grave two to three times a day. He sets up his chair and settles onto the green lawn he cultivated for the past eight months. He fertilizes and takes care of this small patch of grass because this, after all, is the final resting place of his beloved wife.

“I live in Waimanalo, but even if I have something to do I always come back here,” Kaneakua says. As a U.S. Army veteran, he is eligible for a plot for his wife and himself at the cemetery. But he, too, has had difficulties with the bad weather conditions and the sinking tombstones.

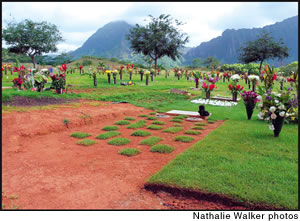

Green gravesites are lush only because families care

for them; grass on the red dirt grave is still growing in

“No one plants grass, and I see the weeds on the other graves below my wife’s. And you can tell no one takes care because the weeds grow all over,” he says. “They’re doing some maintenance, but I don’t know that it’s enough because the headstones sink and the graves sink.

“Six months go by and you can’t just wait to see if they’re going to do anything. If I wasn’t here, the grave would be a mess.”

Indeed, these faithful survivors wonder, who would tend to the graves if relatives were too sick or feeble?

“Mr. Fujimori used to come three times a week, and his area was beautiful, and I don’t know what happened,” says Fujimoto, referring to a nearby gravesite. “He was so nice because he used to water my grass, and now I think he’s sick and I worry about him, because you can tell his grass is dry and not so good.”

Lei Hanawahine, adult corrections officer at the Women’s Community Correctional Facility, brings her crew of inmates over to do yard work every Friday from 7 a.m. to 1 p.m.

“They pick up the dead flowers and weed-whack around the headstones,” Hanawahine says. “These girls work hard — cleaning up the exterior with cane knives, cutting down trees — but the grass is so thick.”

In testimony before the state Department of Defense, Edward Cruickshank acknowledged the problems. “I certainly concur with Rep. (Ken) Ito that our State Veterans Cemetery in Kaneohe is in need of repair, requiring immediate maintenance to stop the escalating deterioration of the columbarium, along with the sinking grave problem,” stated Cruickshank, director of the state Office of Veterans Services.

Cruickshank currently marshalled a bill through the state Legislature to gain more funding to improve the cemetery, successfully acquiring more funds for the 2006-2007 operating budget. The bill is waiting now to be signed by the governor.

State Rep. Ken Ito, operations manager Miles Okamura,

Edward Cruickshank and Maj. Charles Anthony of the state

Department of Defense inspect recent improvements at the cemetery

“We are asking for an increase of $187,450 to purchase dirt, casket liners, and to fix the sprinkler system that has been in disrepair since I was appointed to this position in May 2004,” adds Cruickshank.

Additional funds will be implemented to research the area, and also make additional improvements to the grounds.

The casket liners would be available for any new graves and would prevent the ground from sinking when it deteriorates and collapses.

The dirt would replace fill material used during the cemetery’s construction.

Cruickshank says that the claylike fill does not hold together when compacted, and it washes away in heavy rains, causing the ground to sink. And more funding would also help to repair the sprinkler system, aiding the many senior citizens who have to haul in their own water hoses and water cans.

The cemetery has four to five people working regularly, and they can get up to eight to 10 workers with support from Fort Ruger maintenance.

Edward Cruickshank, director of the

state Office of Veteran Services

Herring Kalua Jr., general labor supervisor, was hired April 1, when funding was released to open the position. “Part of the reason why I took this job was because I got family here and I thought it needed some work, and I wanted to be a part of improving this place,” says Kalua. “I felt guilty, and I thought it could be better. And I understand the funding can be tough, but we could improve the place. Now with funding coming up, I feel that we can really make a difference. I have a vision of what this place could be, and I want to do that.”

Kalua wants to improve the sprinkler system and workflow, being serviceable for the people. In the eight months he has been working at the cemetery, he has been putting up manual sprinklers and repairing the system’s leaks. To prevent further sinking of caskets, Kalua and his crew have been water-tamping the sites, a method they began using a year ago. It involves using water and dirt to compact the area. They use screen dirt — dirt from which large rocks and large pieces have been removed, with water to fill holes that would normally cause sinking, compacting the dirt to get out all of the air pockets.

With additional funding, Kalua says they will be able to purchase better dirt to compact the area. Dirt that is rich with nutrients and mulch will also help the grass to grow better in a shorter amount of time.

“With funding, we can hire contractors, get parts and rates — the funding is important, and when the Legislature gives us the money we can improve this place.”

Currently, Miles Okamura, cemetery operations manager, says “It takes up to six months to complete a row of plots. And when a row is completed, the grass is planted, and that usually takes another three months.”

In the meantime, people like Leah Brooks cannot wait to put grass in their spots. The muddy area and barren ground are a disheartening sight, especially when the grief is fresh.

Former Army sergeant Richard Brooks thought he was lucky to get home, after fighting in Iraq. But he was struck down in a fatal car accident on his return to Hawaii. His remains are at the Hawaii State Veterans Cemetery. Wife Leah waited six months for a headstone and six more months before she decided to plant her own grass. April 22 marked the one-year anniversary of his passing.

“I see the other plots, and the grass planted next to mine is nice,” she says. “I hope that grass moves up to mine. I haven’t seen Richard’s site mowed yet, and I can’t plant grass too well because my knees are bad.”

Lisa Kitagawa (left) and Melissa Peneyra visit

Melissa’s father’s grave

Richard Brooks’ best friend in the military, Don Goss, stood adorned in Indian garb and chanted around the burial ground in an old Apache death ceremony to honor and send off the souls of the dearly departed.

“We dance three times around to represent the circle of life we all live within,” Goss explains. “The moon and sun is a circle, and as we dance in a circle this is what binds us to our grandparents and parents.”

Such ancient practices gave respect and honor to the dead — a tradition that stands in contrast to a world where money makes things happen and the government makes all of the rules. But even in this time we must remember these modern-day warriors.

They gave

To all of us

Freedom

Concerns or questions may be sent to Edward Cruickshank, director, Office of Veterans Services, 459 Patterson Road, E-Wing, Room 1-A103, Honolulu, HI 96819-1522 (433-0420); or to Miles Okamura, operations manager, Hawaii State Veterans Cemetery, 45-349 Kamehameha Hwy., Kaneohe HI 96744, 233-3630.

Page 1 of 1 pages for this story

E-mail this story | Print this page | Comments (0) | Archive | RSS

Most Recent Comment(s):